Welcome to the food protein biophysics laboratory

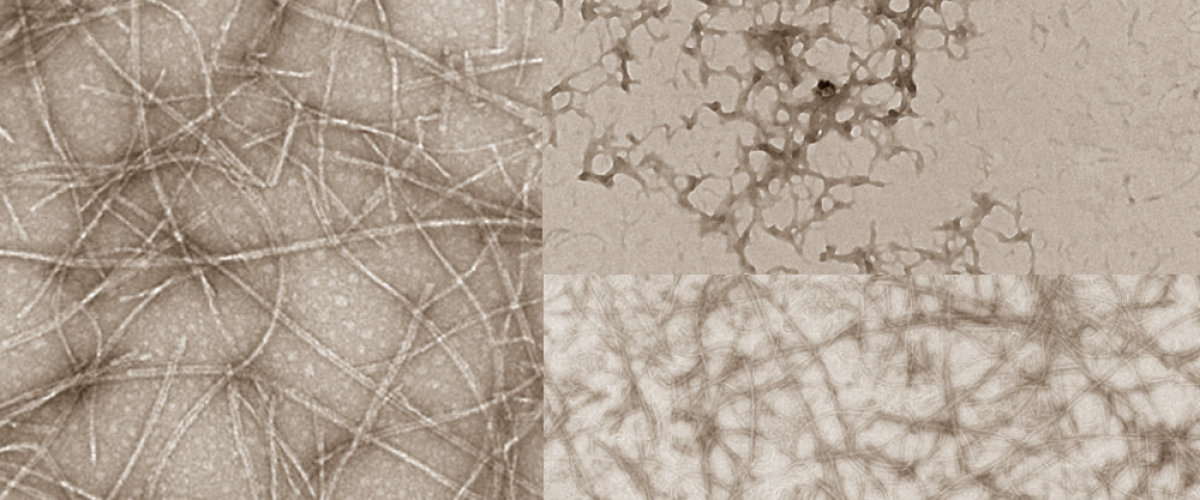

We use biophysical tools and protein engineering to study protein folding and aggregation, particularly amyloid fibrils (aka nanofibrils). Certain amyloid fibrils play a role in disease, while functional protein nanofibrils hold promise for a variety of applications, including as adhesives, cell-culture scaffolding, biosensors, encapsulants and food ingredients. Current projects include the conversion of plant proteins into nanofibrils for use as meat-analogues, and the use of bioconjugation to create functionalized nanofibrils.

People are seeking alternatives to animal protein to improve their health and the sustainability of their diet. Proteins from legumes (such as soy, pea, lentil and chickpea) could further meet this demand, if novel processes are found that improve their functionality in food. The functionality (e.g. texture, gelling and foaming ability, and water and fat binding capacity) of plant proteins is generally lower than that of animal protein and can result in foods with lower consumer acceptability. One promising approach to dramatically alter the functionality of proteins is to induce their self-assembly into long, thin strands called ‘nanofibrils’, which are promising materials in biotechnology. Nanofibrils have a unique structure and surface chemistry that enables them to form films and gels and stabilize foams and emulsions. Nanofibrils have physical properties (tensile strength, elasticity) similar to muscle proteins and thus could serve as a useful building-block for developing meat-like foods using plant proteins.

The challenge is to understand the relationships between the structure of plant proteins and their functionality in foods. Proteins change their molecular shape and aggregate into an array of complex structures, making it difficult to engineer a particular combination of structure and functionality. Most nanofibril research has focused on animal proteins, and a more fundamental understanding of how plant proteins self-assemble into nanofibrils is needed, which we can use to develop improved plant protein ingredients for foods.

New faculty profile: here.

UBC alumni magazine fall 2002: Diversify our food system